SLAC fires up electron gun for LCLS-II X-ray laser upgrade

Its electron beams will drive the generation of up to a million ultrabright X-ray flashes per second.

By Manuel Gnida

Crews at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have powered up a new electron gun, a key component of the lab’s upgrade of its Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser, and last night it fired its first electrons.

Located at the front end of the next-generation machine known as LCLS-II, the gun is part of what is called an injector, which will generate a nearly continuous stream of electrons to drive the production of powerful X-ray beams at a rate that is 8,000 times faster than LCLS to date.

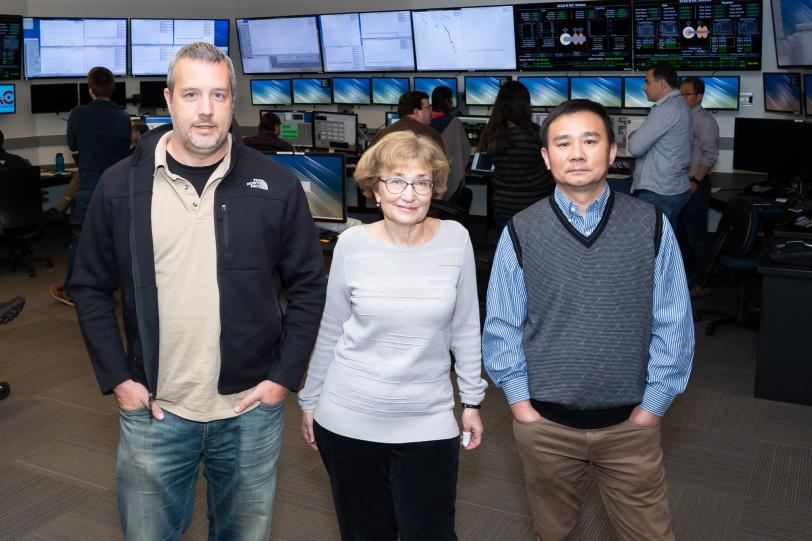

The successful production of electrons was the culmination of the past 15 months, during which teams have installed and tested parts of the injector at SLAC, building on design and testing work over the past few years at DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

“It’s a milestone that shows the complex injector system is working and that allows us to begin the crucial task of optimizing its performance,” said SLAC accelerator physicist Feng Zhou, who is in charge of LCLS-II injector commissioning. “The injector is a very critical system because the quality of the electron beam it creates has a huge effect on the quality of X-rays that will ultimately come out of LCLS-II.”

Making X-rays with electrons

X-ray lasers use pulsed beams of electrons to generate their X-ray light. These beams gain tremendous energy in massive linear particle accelerators and then give some of that energy off in the form of extremely bright X-ray flashes when they fly through special magnets known as undulators.

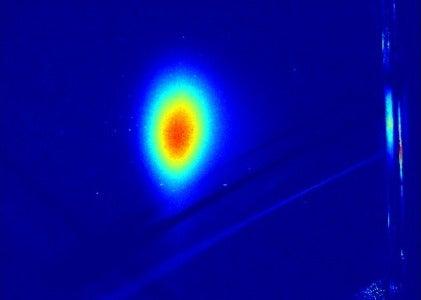

The injector’s role is to produce an electron beam with high intensity, a small cross-section and minimal divergence, the right pulse rate and other properties required to achieve the best possible X-ray laser performance.

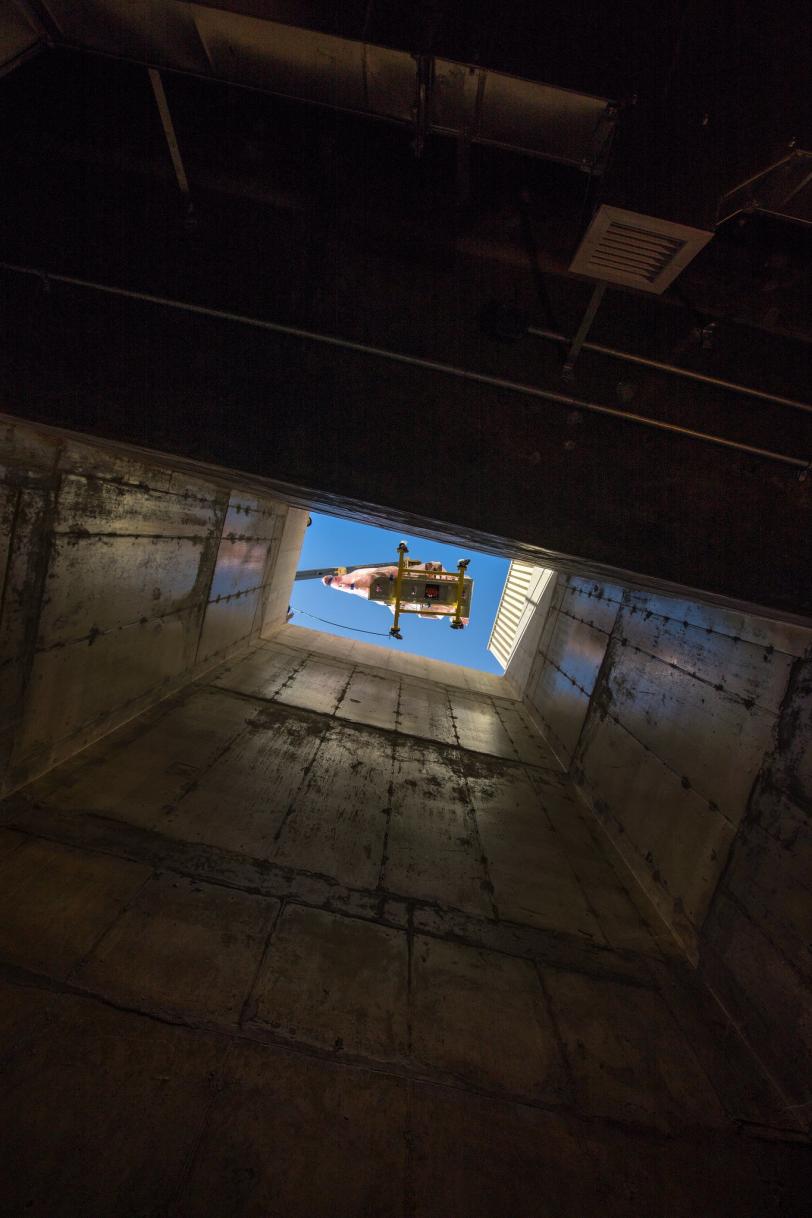

The electrons fired by the injector come from an electron gun. It consists of a hollow metal cavity where flashes of laser light hit a photocathode that responds by releasing electrons. The cavity is filled with a radiofrequency (RF) field that boosts the energy of the freed electrons and accelerates them in bunches toward the gun’s exit.

Magnets and another RF cavity inside the injector squeeze the electrons into smaller, shorter bunches, and an accelerator section, to be installed over the next few months, will increase the energy of the bunches to allow them to enter the main stretch of the X-ray laser’s linear accelerator. Spanning almost a kilometer in length, this superconducting accelerator will increase the speed of the electron bunches to almost the speed of light.

The million-pulse challenge

The most delicate injector component is the electron gun, and for LCLS-II the technical demands are bigger than ever, said John Schmerge, deputy director of SLAC’s Accelerator Directorate.

“The first generation of LCLS produced 120 X-ray flashes per second, which means the injector laser and RF power only had to operate at that rate,” he said. “LCLS-II, on the other hand, will also have the capability of firing up to a million times per second, so the RF power needs to be switched on all the time and the laser has to work at the much higher rate.”

This creates major challenges.

First, the continuous RF field produces a lot of heat inside the cavity. With a power equivalent to about 80 microwave ovens operating at full power at all times, it could damage the electron gun and degrade its performance.

To handle the large amount of power, the LCLS-II gun, which was built at Berkeley Lab, is equipped with a water cooling system. It is also much larger than its predecessor – several feet rather than inches in diameter – so heat is distributed over a larger surface area.

“The LCLS-II project got a flying start, profiting from Berkeley Lab’s experience designing and running this unique electron source,” said SLAC’s John Galayda, who until recently led the LCLS-II project. “It continues to be a great collaboration that is crucial in building the next-generation X-ray laser.”

Another challenge is the laser system, said Sasha Gilevich, SLAC engineer in charge of the LCLS-II injector laser.

“To produce electrons efficiently, we want to shine ultraviolet light onto the photocathode, but there is no commercial laser system capable of providing UV pulses with the unique properties required by LCLS-II at the rate of a million pulses per second,” she said. “Instead, we send the light of an infrared laser through an optical system containing non-linear crystals that convert it into ultraviolet light. But because of the heat generated in the crystals, doing this conversion at such a high pulse rate is very demanding, and we’re still in the process of optimizing our system for the best performance.”

New electron source, new challenges

LCLS-II’s unique capabilities will also rely on a high-efficiency photocathode to produce the initial electron burst. It consists of a flat disc – merely tens of nanometers thick and a centimeter in diameter – of a semiconductor mounted on a metal support. This allows the electrons to be produced about 1,000 times more efficiently than with the copper cathode used previously.

But the advance comes with a trade-off, said SLAC accelerator physicist Theodore Vecchione: “While the copper cathode lasted for years, the new one is not nearly as robust and may last only a few weeks.”

That’s why Vecchione has been tasked with setting up a facility at the lab to fabricate a stockpile of cathodes, which cannot be simply purchased off the shelf, and to make sure the LCLS-II cathode can be replaced whenever needed.

Now that the injector has generated its first electrons, the commissioning team will spend the next few months optimizing the properties of the electron beam and automating the injector controls. However, it won’t be until next year, when LCLS-II’s superconducting linear accelerator has been installed, that they will be able to test the full injector, including the short accelerator section that will boost the electron energy to 100 million electronvolts, and get it ready to do its job of generating some of the most powerful X-rays the world has ever seen.

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit energy.gov/science.